Abstract

This study investigating the differential contribution of self-compassion subcomponents to wellbeing, and examined the effect of age. A total of 275 participants (219 females) completed demographic measures, the Self-Compassion Scale, the Mental Health Index, and a Social Desirability Scale. Hierarchical Multiple Regression indicated that the self-kindness and mindfulness subcomponents predicted wellbeing, whereas the self-judgement, isolation and over-identification subcomponents predicted psychological distress. Furthermore, the negative self-compassion subcomponents accounted for additional variance in psychological wellbeing. Self-compassion was also significantly higher in older adults. This research consolidates previous findings, increases the scope of self-compassion research, and may have practical implications in treatment.

Keywords: self-compassion; wellbeing; age; younger adults

Self-compassion is broadly defined as being open to ones own suffering, being kind to oneself and having the tendency to view inadequacies as part of the larger human experience (Neff, 2003). It is suggested that the state of compassion usually occurs as a result of witnessing someones suffering followed by a subsequent desire to help the sufferer (Goetz, Keltner, & Simon-Thomas, 2010), and it may be closely related to other emotional states such as sympathy, pity and empathy.

Self-compassion has early Buddhist origins, however and , was conceptualised by Neff (2003) as comprising of three main positive components, each of which has an opposing negative component.

The first is self-kindness as opposed to harsh judgement and criticism. Self-kindness involves extending sensitivity and empathy to cognitions, actions and feelings, whereas self-judgement involves being hostile to oneself and rejecting self-worth(Barnard & Curry, 2011).

The second is common humanity rather than isolation. Common humanity is defined as viewing experiences as part of the larger human experience. Conversely, isolation involves feeling alone in ones failures and adverse experiences(Barnard & Curry, 2011).

The last component is mindfulness, rather than over-identification(Neff, 2003). Mindfulness involves having a nonjudgmental mind state and requires attention of the present moment, rather than over-identifying with negative thoughts. Mindfulness requires observing and labelling cognitions and emotions, rather than reacting, which enhances clarity and emotional equanimity(Neff, 2012).

Self-compassion has been theori z s ed as enhancing wellbeing , as it allows for emotional regulation(Neff, 2003) . , and Studying what constructs enhance wellbeing may aid the development of stronger individuals and communities. This may , in turn , influence ways to better buffer against mental health issues, such as depression and anxiety.

It was of interest in the current study to investigate the effect of age on self-compassion, as there are suggestions that initiatives which help younger adults for example, establish common humanity earlier in life , may have improved wellbeing. For example, Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT; Gilbert, 2010) and Mindful Self-Compassion (MSC; Neff & Germer, 2013) aim to help participants develop skills and qualities associated with self-compassion. CFT involves motivating participants to care for their wellbeing and recognise their needs and distress . ; Techniques include mindfulness training, visualisations and performing self-compassionate behaviours. CFT has been successful in aiding people who have a number of disorders (Neff & Costigan, 2014).

Age and self-compassion

Age is an important factor to take into account in order to determine the strength of self-compassion and wellbeing across the lifespan and to examine the association between self-compassion and positive ageing (Phillips & Ferguson, 2013). To date, studies regarding the association between age and self-compassion have produced mixed results. For example, self-compassion was originally theorised to be lower in adolescents compared to older adults, due to the continual process of self-evaluation and social comparison in adolescence, in order to establish identity(Neff & McGehee, 2010). A survey of 385 college undergraduates and 400 community adults (mean ages of 20.92 and 33.27 respectively) found that age was indeed a significant predictor of self-compassion. However, and unexpectedly, self-compassion appeared marginally higher in undergraduates than the older community sample(Neff & Pommier, 2013).

Despite this,Neff (2011)has theorised self-compassion to be higher in older samples due to Eriksons (1966) proposed life stages of Generativity versus Stagnation and Ego Integrity versus Despair. Generativity versus Stagnation involves learning to care for others, which incorporates themes of common humanity. Successful resolution of Ego Integrity involves wisdom, integration, and self-acceptance(Phillips & Ferguson, 2013). (Phillips & Ferguson, 2013) . Although not yet thoroughly studied, self-compassion may be associated with Ego Integrity due to the common associations with acceptance, wisdom, and common humanity(Neff, 2011; Phillips & Ferguson, 2013). Therefore, as participants experience Eriksons stages throughout the aging process, the resolutions may lead to higher levels of self-compassion, and in particular higher levels of common humanity. A study examining self-compassion exclusively in 132 older adults (aged 67-90) found that the mean self-compassion score was 0.7 units higher than found in a college student sample (Allen, Goldwasser & Leary, 2012). However, the mixed results appears to have been affected by age ranges and the current study sought to widen this range and was examined in some detail.

Self-compassion and wellbeing

As well as perhaps being affected by age, there appears a link between self-compassion and the psychological correlates of wellbeing such as life satisfaction, social connectedness, emotional intelligence, wisdom, personal initiative, curiosity, exploration, happiness, optimism, ego-integrity, and meaning in life(Neff & McGehee, 2010; Neff, Rude, & Kirkpatrick, 2007; Phillips & Ferguson, 2013; Raque-Bogdan, Ericson, Jackson, Martin, & Bryan, 2011; Sirois, 2014; Terry, Leary, & Mehta, 2013). Additionally, Neff (2003) found a significant negative correlation between self-compassion and self-criticism, anxiety and depression.

Past findings have shown that self-compassion may deactivate the threat system and activate self-soothing. Germer and Neff (2013) exposed participants to a brief self-compassion exercise and found participants experienced lower levels of cortisol, the principle stress hormone, following the exercise. Thus , self-compassion can subsequently affect hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis activity(Germer & Neff, 2013; Rockliff, Gilbert, McEwan, Lightman, & Glover, 2008). Furthermore, fMRI studies have shown that self-reassurance, which draws parallels with self-compassion, activates the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, left superior temporal gyrus, and insula, all of which are associated with social emotions and monitoring internal states, suggesting that individuals with high self-reassurance have good self-regulatory control related to emotional processing(Longe et al., 2010). These findings highlight that self-compassion can lead to physiological and cognitive changes, which in turn promote wellbeing.

Self-compassion and distress

Self-compassion has been shown to be related to reduced levels of situational anxiety and depression . . In a study examining whe t t h er self-compassion protects against self-evaluative anxiety, 91 undergraduates were exposed to a stressful mock job interview. Participants first completed measures of self-compassion, self-esteem, negative affect, and anxiety before answering two mock job interview questions evaluating their greatest weaknesses. Participants then completed a post-test anxiety measure. Higher self-compassion was related with significantly less anxiety after considering weaknesses, the effect of self-compassion remained significant after controlling for negative affect(Neff et al., 2007). As the study was conducted in a laboratory setting, participants may have experienced less anxiety compared to a high-stakes job interview.

Correlational studies have consistently revealed a negative relationship between self-compassion and depression (Raes, 2011), indicating that self-compassion can enhance wellbeing by protecting against distress. The link between self-compassion, happiness and optimism is theorised to buffer against correlates of depression such as rumination, thus revealing a process by which self-compassion can protect against depression(Neff et al., 2007). In a study comparing self-compassion in 142 clinically depressed patients and 196 never depressed participants, rumination and avoidance were also examined(Krieger, Altenstein, Baettig, Doerig, & Holtforth, 2013). Results indicated that clinically depressed patients were significantly less self-compassionate than never depressed patients. Further, higher levels of self-compassion were significantly negatively associated with rumination and avoidant functioning, both of which are related to depression(Krieger , et al., 2013; Raes, 2010; Samaie & Farahani, 2011). These findings were further supported bySamaie and & Farahani (2011)who found that high levels of self-compassion function to attenuate the link between rumination and negative symptoms.

Self-compassion subcomponents

Only a portion of studies have examined self-compassion at a subcomponent level, however, and such research may be integral to understanding the relationship between self-compassion and wellbeing for important practical implications(Gilbert, Baldwin, Irons, Baccus, & Palmer, 2006; Van Dam, Sheppard, Forsyth, & Earleywine, 2011; Woodruff et al., 2013). Neff (2003) defined six inter-correlated subcomponents, which represent the higher order factor of self-compassion: self-kindness, self-judgement, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness and over-identification(Neff, 2003).

Few studies have evaluated these self-compassion subcomponents in regard to overall wellbeing.Van Dam et al. (2011) did examin e d the effectiveness of the self-compassion subcomponents to predict quality of life and symptom severity compared to mindfulness. Self-compassion subcomponents significantly predicted anxiety, depression, worry and quality of life. Symptoms of anxiety and worry were significantly predicted by self-judgement, isolation, and over-identification, whereas depressive symptoms and quality of life were predicted by self-kindness, self-judgement, isolation, and mindfulness. Analysis revealed that the self-compassion subcomponents contributed three times as much variance as mindfulness. Similar to previous research However , common humanity did not emerge as a significant predictor . Common humanity has been consistently found to bear a non-significant relationship with wellbeing ; however, even though it is theorised to have an essential relationship with the other self-compassion subcomponents, including being an important mechanism to aid mindfulness(Van Dam et al., 2011).

A limitation of past research is that it has not addressed whether the relationship between self-compassion and wellbeing is due to high levels of the positive self-compassion components (i.e. self-kindness, common humanity and mindfulness), or low levels of the negative components (i.e. self-judgement, over-identification and isolation). In order to expand self-compassion research, it may be important to identify the active components of self-compassion(MacBeth & Gumley, 2012).Phillips and Ferguson (2013)proposed that specific self-compassion subcomponents may drive relationships between total self-compassion and wellbeing measures. Thus , an examination of which self-compassion components predict indicators of wellbeing may reveal how self-compassion produces advantageous effects. The aim of the current study was to examine how the aspects of self-compassion , differentially relate to wellbeing and to determine the effect of age on self-compassion.

The current study focused on examining how the subcomponents of self-compassion differentially predict wellbeing and psychological distress, thus and whether it is the existence of the positive components or the absence of the negative components that predict wellbeing. If certain components of self-compassion contribute more to wellbeing than others components, it may allow for specific interventions to increase wellbeing. Wellbeing in the current study included an overall measure, which represented greater positive affect, greater positive ties and life satisfaction and less depression and anxiety.

Participants

The study consisted of 275 (219 female, 56 male) participants recruited using the University participant pool and social media. Participants were aged between 18 and 82 ( M age = 38.20, SD = 17.67). The sample was well educated; 19.6% of participants highest level of education was postgraduate, 32% undergraduate, 19.3% had a diploma/TAFE qualification and 22% had a high school education. The sample was predominantly students or full time workers (30.5% and 31.3% respectively); 13.1% were employed part-time; 6.5% were casual workers; 5.1% were unemployed; and 12.7% were retired. The majority of the sample were Australian (72.4%) other nationalities represented were New Zealand 7.6%, British 6.9%, American 4.7% and European 2.5%, others included Canadian, Indian, Chinese, South African, Nigerian, Nicaraguan, Malaysian and Filipina.

Materials

Demographic questionnaire. Participants were presented with seven demographic questions related to age, gender, education level (high-school, diploma/TAFE, undergraduate, postgraduate) employment (student, casual, part-time, full-time, retired), nationality and ethnicity (both of which were free response questions).

Self- compassion Scale (SCS; Neff, 2003). The SCS was used to measure self-compassion. The SCS is designed for community samples aged 14 and above. The SCS is a 26-item measure composed of six subscales: self-kindness, self-judgement, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and over-identification. Participants were instructed to indicate how often they behave in the stated manner. Items were rated on a five- point scale, ranging from 1 = almost never to 5 = almost always . An example item of positive self-compassion is, When things are going badly for me, I see the difficulties as part of life that everyone goes through. . A negative self-compassion item is, I am disapproving and judgemental about my own flaws and inadequacies. Total self-compassion scores were calculated by reverse scoring the negative subscale items, and then computing a total mean. Higher scores indicate higher self-compassion.

The SCS reports high internal consistency; past ChronbachsCronbachs alphas have been reported as = .92(Van Dam et al., 2011). The ChronbachsCronbachs alpha in this study was =. 93. Test-retest reliability examined over a three week period on undergraduate students was reported as r = .93, indicating high reliability(Neff, 2003). Each of the subscales also displayed high adequate test-retest reliability (Self-kindness = 0.7, 5Self-judgement = 0.77, Common humanity = 0.62, Isolation = 0.56, Awareness = 0.76, Overidentification = 0.73). The SCS was split into subscales as well as total positive and negative self-compassion scores, as recommended byGilbert, McEwan, Matos, and Rivis (2011). The SCS was selected, as it is a readily available measure of self-compassion and displays strong psychometric properties.

Mental Health Inventory (MHI;Veit & Ware, 1983). The MHI is a 38-item self-report scale of general wellbeing (Mental Health Index, referred to as the Wellbeing index in this study and defined as feeling cheerful, interest in and enjoyment of life), consisting of six factors: anxiety, depression, emotional ties, general positive affect, life satisfaction, and loss of behavioural emotional control. In this study, the loss of behavioural control subscale was removed not used, as the questionsit may have caused unnecessary distress for participants who would not have any support while completing the measure. (tThis was recommended by the ethics committee). Items are rated on a six- point frequency scale. Example items are 1 = Extremely happy, could not have been more satisfi ed or pleased , to 6 = Very dissatisfied, unhappy most of the time . Each subscale is scored by adding corresponding items, with higher scores indicating higher levels of the affective state. The Wellbeing Index was calculated by recoding and summing the items. Higher scores on the Wellbeing Index reflect frequent occurrence of favourable mental health symptoms, including high positive affect and low anxiety and depression(Veit & Ware, 1983).

The MHI reports high internal consistency; past ChronbachsCronbachs alpha have been reported as = .92(Veit & Ware, 1983). The scale also reports satisfactory test-retest after one year r = .63(Veit & Ware, 1983). Factor analysis has consistently revealed a higher order factor structure composed of two correlated factors, psychological distress and wellbeing, which are defined by five lower order factors(Veit & Ware, 1983). In the current study, the distress and wellbeing scores were used. The distress scale consists of anxiety and depression measures whereas wellbeing is a total score of positive ties, positive affect, and life satisfaction. For the moderation analyses the Wellbeing Index score was used as it represents greater psychological wellbeing and less psychological distress.

Marlow -Cr owne Social Desira bility Scale short version (SDS;Ray, 1984). The SDS was incorporated to control for social desirability as some participants were students who may have received credit for being involved. The SDS is an eight-item scale; participants were instructed to answer yes or no. An example item is, Are you always courteous, even to people who are disagreeable? Higher scores indicate higher levels of social desirability, in which case answers should be interpreted with caution. The SDS reports satisfactory reliability; the original author Ray administered the SDS to a random mail-out and doorstep sample, and ChronbachsCronbachs alpha alpha was reported as = .77(Ray, 1984).

Procedure

The online questionnaire was constructed on Psychdata software (Locke & Keiser-Clark, 2001). Participants were recruited using social media and the University participant pool and asked to participate in an anonymous web-based questionnaire assessing compassion and wellbeing. Participants completed the study on their personal computer or mobile device and were not given a time limit. The researchers were not present while participants completed the study, and therefore location is unknown. All participants read the explanatory statement before granting informed consent, which was gained electronically. Demographic details (age, gender, education, employment, nationality and ethnicity) were collected. Participants then completed the MHI, followed by the SDS and SCS. Before each scale, participants received instructions on how to answer the questions. Upon completion of the study, participants were thanked for their involvement; participants recruited through the University participant pool were granted 0.5 study credits for their participation. Those who participated through social media did not receive anything.

Results

Prior to running the analysis, the data was screened for errors or missing values using visual analysis and frequency statistics. Visual analysis revealed 40 participants who did not complete the demographic section or the first scale and these were removed. The sample size was assessed for both regression and ANOVA analysis, for which a minimum of 252 participants were required. Sample size was assessed using Tabachinck and & Fidells (2013) formula N> 50 + 8m. T, thus, the sample size needed to be greater than 130 participants. The final sample size of the current study was 275 and was deemed large enough for the selected analysis.

Univariate outliers were investigated using box and whisker plots; analysis revealed three univariate outliers on the distress scale, however no extreme outliers were identified and none were therefore not removed from the analysis. Multivariate outliers were assessed using Mahalonobis distances, and; no extreme multivariate outliers were evident.

Hierarchical multiple regression, moderation and one way ANOVA analyses were conducted and the criterion for significant results was set to =. 05 unless otherwise specified. The statistical assumptions of hierarchical multiple regression and ANOVA were assessed separately.

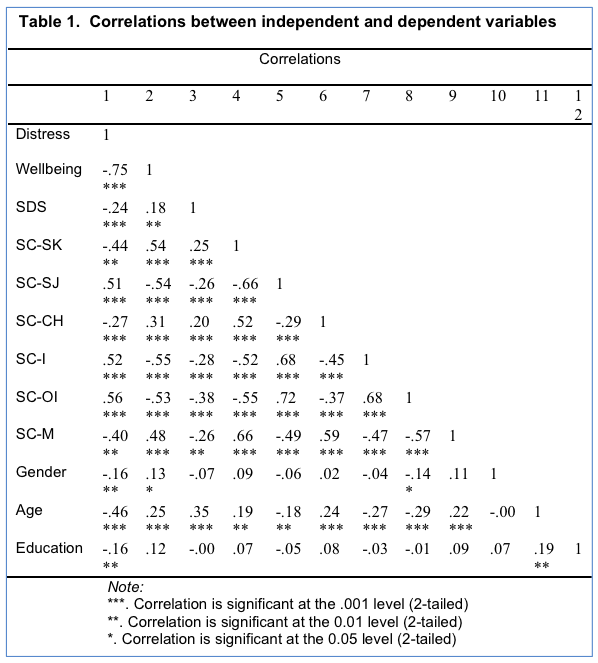

Table 1 shows the correlations between all dependent and independent variables, and indicates an absence of singularity. Inspection of tolerance/VIF vales revealed an absence of multicollinearity amongst the variables.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression 1: Self-compassion as predictors of wellbeing

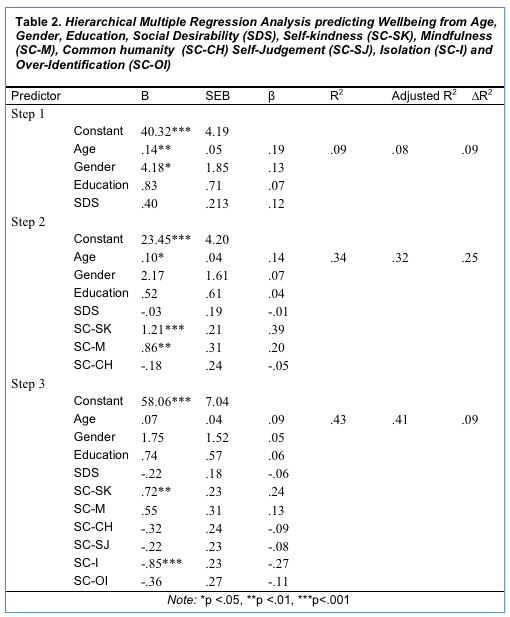

The first hierarchical multiple regression assessed the ability of all the self-compassion subcomponents to predict psychological wellbeing, controlling for age, gender, education and social desirability. It was anticipated that self-kindness and mindfulness would predict psychological wellbeing and have a positive association and that the negative self-compassion components would account for additional variance of wellbeing.

Age, gender, education, and social desirability in order to control for their impact, were entered at Step 1 to control for these variables, explaining 9.5% of the variance in psychological wellbeing F (4,267) = 7.04, p <. 001. After the positive self-compassion components were entered in Step 2, the total variance explained by the complete model was 34.2%, F (7,264) = 19.57, p <. 001. The positive self-compassion subcomponents explained an additional 24.6% of the variance in psychological wellbeing, after controlling for gender, age, education and social desirability, F change (3,264) = 32.92, p <. 001. In step 2, only age, self-kindness and mindfulness significantly predicted psychological wellbeing. The negative self-compassion components were added in Step 3; the whole model explained 43.3% of the total variance in psychological wellbeing, F (10,261) = 19.91, p < .001. The negative self-compassion subcomponents uniquely explained 9.1% of variance in psychological wellbeing, after controlling for the control variables and positive self-compassion subcomponents, F change (3,261) =13.98, p <. 001. In the final model only isolation and self-kindness were significant (see Table 2)

Hierarchical Multiple Regression Negative self-compassion as predictors of distress

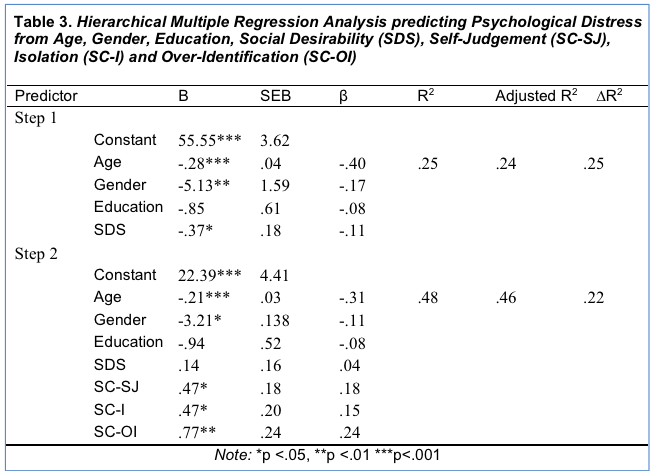

The second hierarchical multiple regression was run to determine the ability of the negative self-compassion components: self-judgment, over-identification and isolation as predictors of psychological distress, controlling for age, gender, education, and social desirability. It was hypothesised that self-judgement, over-identification and isolation would predict distress and have a positive association.

Age, gender, education and social desirability were entered in Step 1 to control for these variables, explaining 25.4% of the variance in psychological distress F (4,267) = 22.66, p <. 001. After self-judgement, isolation, and over-identification were entered at Step 2; the whole model explained 47.5% of the total variance of psychological distress F (7,264) = 34.08, p <. 001. The negative self-compassion components explained an additional 22.1% of the variance in psychological distress, F change (3,264) = 37.05, p <. 001. In the final model, age, gender and all the negative self-compassion components were statistically significant (see Table 3).

Post-Hoc ANOVA: E ffect of age on self-compassion

A one-way between-groups ANOVA was conducted to explore the impact of age on levels of total self-compassion. Using visual binning on SPSS, participants were equally divided into three groups according to their age (Group 1: 24 years or less, Group 2: 25-50 years, Group 3: 51 years and above). Group 1 had 93 adults (35%), group 2 had 96 adults (35%) and group had 83 adults (30%). Analysis revealed there was a statistically significant difference in total self-compassion scores for the three age groups, F (2,269) = 15.16, p <. 001. The effect size was moderate to large at p2 = .10. Post-hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test indicated that the mean score for group 3, ( M = 91.27, SD = 17.71) was significantly different from group 2, ( M = 80.57, SD = 16.95), p <. 001, d = .6 , and group 1, ( M = 77.65, SD = 16.76), p <. 001, d = .7 . Group 1 and 2 did not differ significantly in self-compassion scores, p =. 47.

The present study aimed to investigate how the six subcomponents of self-compassion differentially contribute to psy c c h ological w ellbeing and to establish a clearer understanding of the role age plays in self-compassion. The regression analysis revealed that both self-kindness and mindfulness significantly predicted wellbeing and had a positive association. Similarly, regression analysis found the negative subcomponents accounted for an additional 9.1% of variance of wellbeing. However, in the final model, only self-kindness and isolation remained as significant predictors. As the negative components contribute unique variance to wellbeing, it is clear the negative subcomponents, particularly isolation, play an important role in measuring self-compassion.

Hierarchal multiple regression analysis revealed all three negative subcomponents predicted psychological distress in a positive direction. Therefore, the positive components, with the exception of common humanity, predicted wellbeing, whereas the negative components predicted psychological distress. These results suggest that self-kindness and isolation are the most influential predictors of wellbeing in the current sample. Therefore, treatment initiatives in counselling and self-compassion programs may benefit most from focusing on decreasing isolation and increasing self-kindness.

The regression analysis revealed common humanity was not a significant predictor of wellbeing; however , this finding was consistent with previous research. Moderation analysis revealed common humanity was not a significant moderator of self-compassion and wellbeing. This has not been previously studied; however, I i t has been proposed that common humanity bears an important relationship in enhancing the remaining subcomponents . This unexpected finding may reveal common humanity is only prevalent in certain samples such as older participants. If but if common humanity does not significantly predict outcome measures, nor impact the relationship between the remaining components and wellbeing, it may not be as integral to self-compassion as originally theorised.

The current study also examined whether the negative subcomponents would moderate the relationship between the positive self-compassion subcomponents and wellbeing. This has not previously been analysed; nevertheless, it is theorised that the subcomponents mutually enhance one another. For example, Ying (2009) proposes that mindfulness reduces the likelihood of self-blame, which in turn aids self-kindness. However, moderation analysis in the current study revealed a non-significant interaction between the positive and negative self-compassion subcomponents. Thus, the negative subcomponents did not significantly moderate the relationship between positive self-compassion and wellbeing.

Age was also examined in the current research. Past research has found mixed findings regarding age due to restricted ranges. T T h e current study utilised a sample aged between 18 and 82. First , ly it was proposed that self-compassion would be higher in older adults compared to younger adults, as they often self-evaluate and engage in social comparison in order to establish identity. Self-compassion was significantly higher in the eldest age group compared to the middle and young age group and . r R esults displayed a strong effect size. There was no significant difference between the young and middle age group, which may explain why previous studies failed to find a significant difference (Neff & McGehee, 2010; Neff & Pommier, 2013). The current findings further support theory proposed by Neff (2011), who theorised self-compassion would be higher in older age groups, due to the resolutions of Eriksons (1966) final two stages of development.

It was also thought age would moderate the relationship between self-compassion and wellbeing. As self-compassion was found to be higher in older adults, it was proposed that at higher ages, the effect of self-compassion on wellbeing would be stronger. However, moderation analysis revealed age was not a significant moderator of the association between self-compassion and wellbeing. Despite the unexpected nature of this finding, it adheres to previous meta-analyses which found age did not moderate the relationship between self-compassion and outcome variables (MacBeth & Gumley, 2012) . This finding may be due to more than half the sample (69%) falling in the 18-50 years age bracket, with a smaller proportion of participants aged 51 and over. This indicates that there may have been an insufficient spread of ages to reveal a moderation effect. Furthermore, there may be other variables that impact wellbeing in older adults such as physical health or increased stress; future research controlling such factors may reveal a clearer relationship between age and self-compassion.

Common humanity has previously displayed a non-significant relationship with wellbeing (Van Dam et al., 2011). However, due to he resolutions of Eriksons (1966) stages, it is theorised that common humanity may be higher in older participants. It was anticipated that at older ages, the effect of common humanity on wellbeing would increase. Moderation analysis revealed a significant moderation of age on common humanity. As age increased, the effect of common humanity on wellbeing became significant, and the slope to predict overall wellbeing from common humanity became stronger. Consequently, common humanity, the ability to view negative experiences as part of the human experience, may develop with age throughout Eriksons stages. As such, therapists or mental health practitioners may be able to augment their training and therapeutic methods with regards to common humanity to ensure that its impact is reflected in developing wisdom of self-compassion for younger people.

When interpreting the results of the current research, consideration should be given to the limitations of the study. The cross-sectional, non-experimental design of the study constrains the inferences that can be drawn. As the current study was cross-sectional, any inferences regarding the trends of self-compassion across the lifespan should be approached with caution. Cross-sectional research limits the ability to determine whether self-compassion develops as a result of age, as all variables were measured simultaneously. Future research would benefit from employing a longitudinal design to investigate how self-compassion develops over the lifespan. Furthermore, as the study was non-experimental, causality cannot be inferred . H ; h owever, self-compassion research has begun employing experimental designs, confirming the direction of the relationship between self-compassion and wellbeing (Leary et al., 2007; Neff et al., 2007). Although the study is limited by its design, the research makes a significant contribution to self-compassion research. Further, the surveys were self-report, and response bias may be evident. Finally, the majority of the sample was female and Caucasian, and 70% were under the age of 50. These factors would have impacted the results.

Despite the limitations, the current research contribute s d to self-compassion research by consolidating previous findings and increasing the scope by including self-compassion sub-components. The practical implications of the current research include a direction for treatment in counselling and self-compassion programs. Indeed, two programs have already evolved from self-compassion research: Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT; Gilbert, 2010) and Mindful Self-Compassion (MSC; Neff & Germer, 2013). Future research would benefit from further investigation of the impact of self-compassion subcomponents across the lifespan. Utilising self-compassion to promote wellbeing may allow for the development of stronger individuals and hence communities, in addition to enhancing our ability to protect against and treat mental illness.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (Bond University Human Research Ethics Committee).

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

References

Baer, R. A., Lykins, E. L. B., & Peters, J. R. (2012). Mindfulness and self-compassion as predictors of psychological wellbeing in long-term meditators and matched nonmeditators. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 7 (3), 230-238. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2012.674548

Cooper, C., & Pervin, L. (1998). Personality . London: Routledge.

Erikson, E. H. (1966). Eight ages of man. International Journal of Psychiatry, 2 , 281-300. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/psycinfo/1967-08667-001

Germer, C. K., & Neff, K. D. (2013). Self-compassion in clinical practice. J ournal of Clin ical Psychol ogy , 69 (8), 856-867. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22021

Gilbert, P. (2010). An introduction to compassion focused therapy in cognitive behaviour therapy. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy , 3, 97112.

Gilbert, P., Baldwin, M., Irons, C., Baccus, J., & Palmer, M. (2006). Self-criticism and self warmth: an imagery study exploring their relation to depression. Journal of Cogntiive Psychotherapy, 20 , 183-200. doi: 10.1891/088983906780639817

Gilbert, P., McEwan, K., Matos, M., & Rivis, A. (2011). Fears of compassion: development of three self-report measures. Psychological Psychotherapy, 84 , 239-255. doi: 10.1348/147608310X526511.

Goetz, J. L., Keltner, D., & Simon-Thomas, E. (2010). Compassion: An evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychological Review , 136, 351374.

Hayes, A.F. (2013). An introduction to mediation, moderation and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Krieger, T., Altenstein, D., Baettig, I., Doerig, N., & Holtforth, M. G. (2013). Self-compassion in depression: associations with depressive symptoms, rumination, and avoidance in depressed outpatients. Behav iour Ther apy , 44 (3), 501-513. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2013.04.004

Longe, O., Maratos, F. A., Gilbert, P., Evans, G., Volker, F., Rockliff, H., & Rippon, G. (2010). Having a word with yourself: neural correlates of self-criticism and self-reassurance. Neuroimage, 49 (2), 1849-1856. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.09.019

MacBeth, A., & Gumley, A. (2012). Exploring compassion: a meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clin ical Psychol ogy Rev iew , 32 (6), 545-552. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.06.003

Mills, A., Gilbert, P., Bellew, R., McEwan, K., & Gale, C. (2007). Paranoid beliefs and self-criticism in students. Clin ical Psycho logy and Psychother apy , 14 (5), 358-364. doi: 10.1002/cpp.537

Neff, K. D. (2003). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self an d Identity, 2 , 223-250. doi: 10.1080/15298860390209035

Neff, K. D. (2011). Self-compassion, self-esteem and wellbeing. Social and Personality Psychology, 5 , 1-12. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00330.x

Neff, K. D., & Costigan, A. P. (2014). Self-compassion, wellbeing and happiness. Psychologie in Osterreich, 2 , 114-199. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22076

Neff, K. D., Kirkpatrick, K. L., & Rude, S. S. (2007). Self-compassion and adaptive psychological functioning. Journal of Research in Personality, 41 (1), 139-154. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2006.03.004

Neff, K. D., & McGehee, P. (2010). Self-compassion and psychological resilience among adolescents and young adults. Self and Identity, 9 (3), 225-240. doi: 10.1080/15298860902979307

Neff, K. D., & Pommier, E. (2013). The Relationship between self-compassion and other-focused concerm amoung college undergraduates, community adults and practicing mediators. Self and Identity, 12 , 160-176. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2011.649546

Neff, K. D., Rude, S. S., & Kirkpatrick, K. L. (2007). An examination of self-compassion in relation to positive psychological functioning and personality traits. Journal of Research in Personality, 41 , 908-916. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2006.08.002

Phillips, W. J., & Ferguson, S. J. (2013). Self-compassion: a resource for positive aging. Journal of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences , 68 (4), 529-539. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs091

Raes, F. (2010). Rumination and worry as mediators of the relationship between self-compassion and depression and anxiety. Personality and Individual Differences, 48 (6), 757-761. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.01.023

Raes, F. (2011). The Effect of self-compassion on the development of depression symptoms in a non-clinical sample. Mindfulness, 2 (1), 33-36. doi: 10.1007/s12671-011-0040-y

Raque-Bogdan, T. L., Ericson, S. K., Jackson, J., Martin, H. M., & Bryan, N. A. (2011). Attachment and mental and physical health: self-compassion and mattering as mediators. J ournal of Couns elling Psychol ogy , 58 (2), 272-278. doi: 10.1037/a0023041

Ray, J. J. (1984). The reliability of short social desirability scales. The Journal of Social Psychology, 123 , 133-134. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1984.9924522

Rockliff, H., Gilbert, P., McEwan, K., Lightman, S., & Glover, D. (2008). A pilot exploration of heart rate variability and salivary cortisol responses to compassion-focused imagery. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 5 , 132-139. doi:10.1038lmp.2012.2

Samaie, G., & Farahani, H. A. (2011). Self-compassion as a moderator of the relationship between rumination, self-reflection and stress. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 30 , 978-982. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.190

Shaddish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal i nference . Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Sirois, F. M. (2014). Procrastination and Stress: Exploring the role of self-compassion. Self and Identity, 13 (2), 128-145. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2013.763404

Terry, M. L., Leary, M. R., & Mehta, S. (2013). Self-compassion as a buffer against homesickness, depression, and dissatisfaction in the transition to college. Self and Identity, 12 (3), 278-290. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2012.667913

Van Dam, N. T., Sheppard, S. C., Forsyth, J. P., & Earleywine, M. (2011). Self-compassion is a better predictor than mindfulness of symptom severity and quality of life in mixed anxiety and depression. J ournal of Anxiety Disord ers , 25 (1), 123-130. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.08.011

Veit, C. T., & Ware, J. E. (1983). The structure of psychological distress and well-being in general populations. Journal of Counsulting and Clinical Psychology, 51 , 730-742. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.51.5.730

Wagner-Moore, L. E. (2004). Gestalt Therapy: past, present, theory, and research. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 41 (2), 180-189. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.41.2.180

Woodruff, S. C., Glass, C. R., Arnkoff, D. B., Crowley, K. J., Hindman, R. K., & Hirschhorn, E. W. (2013). Comparing Self-Compassion, mindfulness, and psychological inflexibility as predictors of psychological health. Mindfulness, 5 (4), 410-421. doi: 10.1007/s12671-013-0195-9

Ying, Y.W. (2009). Contribution of self-compassion to competence and mental health in social work students. Journal of Social Work Education, 45 , 309-323. doi: 10.5175/jswe.2009.200700072